Many Sights Left Unseen

(AKA How I Learned to Embrace My Disability at the Adaptive Climbing Festival) by Seneida Biendarra, ACF Travel Scholarship Recipient

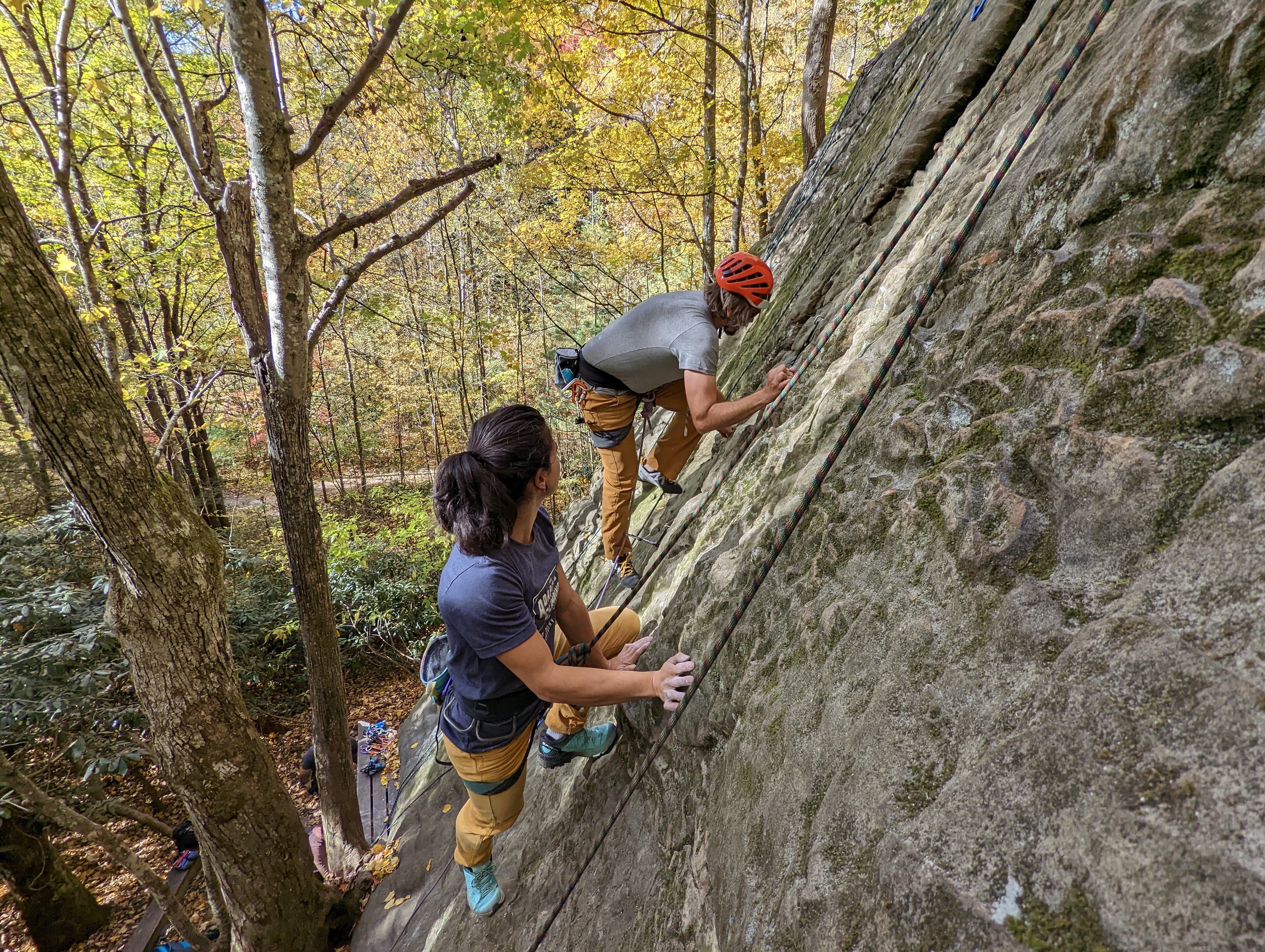

Seneida looks up at a climb, photo by Lindsay Foy

I’ve been a rock climber for seven years, and I’ve been losing my vision for eight... And while all my friends know I enjoy climbing, it’s only a few that are aware that I’m blind. At the ACF, for the first time I embraced the “adaptive” in me and spent the weekend reveling in the freedom that comes with “saying the quiet part out loud”. I’d never had the opportunity to put that part of myself out there, it took a festival of amazing adaptive climbers for me to feel comfortable being differently abled.

Between being a climber and blind, one identity masks the other, in a way. If I disclose to someone I had just met that I was visually impaired, I could expect their interactions with me to change more than if I got stoked telling an awesome story about an all-day climbing epic, then mention “...and actually, I’m legally blind”. It’s like a weird math equation where my outdoor pursuits cancel out my impairment and then I’m spared the well-intentioned but patronizing help from those who aren’t aware that blindness is a spectrum.

Derek, a blind climber, learns to clean achors. By Lindsay Foy

Only 20% of those with visual impairment are totally blind - that is, to have no perception of light and dark. The rest of us have a range of visual acuity that presents in vastly different ways, condition to condition and person to person. Regardless of if one’s vision is partially obscured, distorted, or has little contrast sensitivity, it can be difficult to explain to those around us how we see and what we’re comfortably capable of. Especially once the B-word comes into play.

I have a genetic condition referred to as Retinitis Pigmentosa, which affects the light-sensitive rod cells in my retinas. While I lived the first 17 years of my life with complete vision, it was just as I was about to enter adulthood that the first symptoms arose. The edges of my vision began to degrade, and where I previously was an intuitive athlete, suddenly I couldn’t catch a ball or react quickly enough to my surroundings. I ran into posts and doors, fell down stairs and got lost in the dark. The night sky lost its luster as the stars blurred, faded, then disappeared. Within a few years, my visual field shrank from 180 degrees to less than 5. It never felt real, it was too slow to understand what was happening and I’d never quite accepted that daily life was going to change.

In rock climbing, I found a sport where I didn’t feel different. If I had the patience and endurance to hang out until I could spy the next hold, I could climb just as hard as my friends. Where my appetite for fast-moving sports soured, climbing provided a space where movement was controlled and deliberate. The abundant crack climbing at Devil’s Lake was very friendly, I didn’t need to look for holds- for the most part, I just needed to follow the natural line! Often, navigating the steep talus trail up to the crag would prove more frustrating than the climbing, where I felt like I was back in control.Throughout college I traveled on road trips to Red Rocks, Bishop, and Joshua Tree to climb, chased by the nagging thought that “I should do as much of this now while I can still see.”

It’s never been easy to plainly admit to my friends and peers that “I’m blind”, usually I beat around the bush for a while and make excuses when I walk into walls or stumble or explain that I don’t drive. “Oh, I just have bad vision”. It feels strange when it feels like you CAN see to use a word that associates you with the shades, dog, and cane - So I didn’t tell my peers in school, at work, or at the crag. When the general understanding of blindness is binary, it’s easy to hide an “invisible disability”- no one can look at you and know the truth of your condition.

In the outdoor community, I wasn’t sure if I’d have the opportunity to meet other climbers like me… but I had wanted to, I just didn’t know how to reach out. The only adaptive climbers I knew of felt like celebrities to me (lol), and I was too insecure to openly ask the Mountain Project community if there were others out there with visual impairments. The ACF was attended by the absolute BEST crowd I ever could have imagined. It was like suddenly, I was surrounded by the only people I’d ever met who felt the same things I did, who had their own story of loss or feeling isolated by their disability. Everyone was open about themselves, and for the first time I felt compelled to open up and tell my own story.

Seneida, left, chats with other disabled climbers at Base Camp. Photo by Lindsay Foy

The 2022 Adaptive Climbers Festival presented itself as that rare chance to mingle with what I'd say was the most unique group of people I'd ever met. Boy, was I nervous, though. I'd never been to an Adaptive-specific anything, plus mentally I didn't want to accept that I would belong at an adaptive event. I've already been climbing for a while, so I questioned if it was worth traveling to Kentucky for a weekend if I wasn’t coming back with a bunch of new climbing skills. Spoiler alert ⚠️ It was more than worthwhile, those four autumn days at the Red River Gorge were the most fun I'd had and the most honest I've felt in a while. Though I maybe didn’t leave a better climber, I found a hundred new friends I would never have otherwise - and their pure stoke was enough to encourage me to aim higher, push harder, and be proud to call myself an “adaptive climber”.

Putting this out there - above anything this weekend was FUN. For all the personal growth, there was equal part rowdy! It’s rare that a costume party that goes full send the way the ACF crowd did for the TOGA PARTY!! I won’t spoil too much, you’ll have to come in 2023 to experience it for yourself!

In the Blind Climbing Club, I was able to meet other VI athletes and learn about their techniques for navigating the rock face with limited or no vision. I’d not really learned much about the process of “calling” before, wherein the belayer on the ground reads and describes the route to the VI climber. I had heard of it, but I’d mostly climbed without any such system. I’d ask my belayer to tell me when I was at the bolt while sport climbing (the ones in front of my face are always the hardest to find!!), but I left the hold-finding to myself- at the cost of time and any sense of flow. Putting on the headset for the first time, I was excited how much smoother the climbing experience was when I was directed towards the next likely jug, crimp, or pocket. Each VI had devised their own system for calling with their partner, but none of our usual partners were there! This gave me the chance to try being a caller for a climber with total blindness as he worked up a steep, pocket-y route. Though my attempt at calling was marginal at best, he stoically worked his way up the face with the methodical endurace of someone who has to hang patiently while feeling for their best option. Damn. These are my homies.

Volunteer Nina coaches blind climber Trevor on his first lead climb. Photo by Matt Chao

Rock presents itself the same way to every climber that approaches its puzzle, and it’s up to the climber to figure out how to use their body to find their solution. Adaptive climbing is so rad in part because it takes the personal challenge to another level - everyone’s beta is novel to their own way of adapting their disability. It was so cool to see everyone sharing and practicing each others creative methods of making climbing work for them. It felt like being in an earlier era of climbing where there was no precedent and it was up to each team to figure out "how" as they went. RAD.

I had previously thought that I had been a determined person “in spite” of my disability, but after a weekend at ACF it was clear from meeting the incredible athletes that many there had determined personalities because of their disabilities. And where everyone is different, no one is different - so at the end of each day, we shared the warmth of the fire and like any other group of adventurers, passed a drink, told old climbing stories, and made big plans for tomorrow.

See ya in 2023!